Gilded Garden

The nature of love

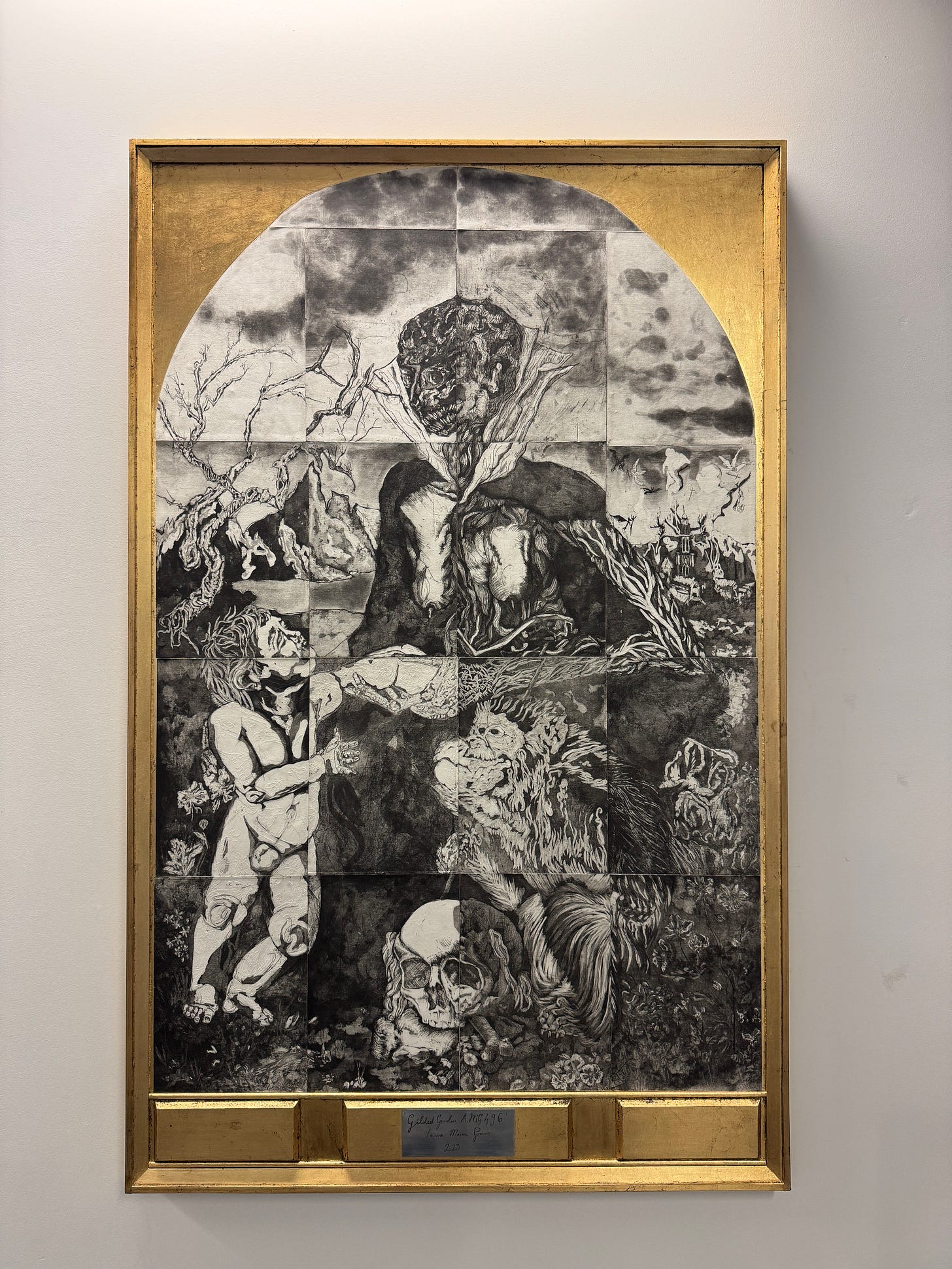

In a grey corridor of New Adelphi building at Salford University hangs Gilded Garden, an artwork by Laura Moxon-Groves: a grid of etchings inside a heavy gilded frame. In an apocalyptic wasteland, a child looks up at a skeletal mother with hollow eyes and sharp teeth; her breasts hang empty, a skull lies at her feet, and a monkey crouches beside her. I first saw the artwork at our Fine Art graduate show in 2023 and found it uncomfortably familiar. It was taunting, as if knowingly staring back at me.

I have always been drawn to mothers where something feels amiss. Mothers who are not quite safe. Mothers who both attract and terrify. Mothers devoid of sentiment. Perhaps my attraction to these uneasy mothers is my way of searching for external evidence, some visual language that mirrors my own conflicting feelings about having been mothered. My own fragmented attachment echoed in the Gilded Garden.

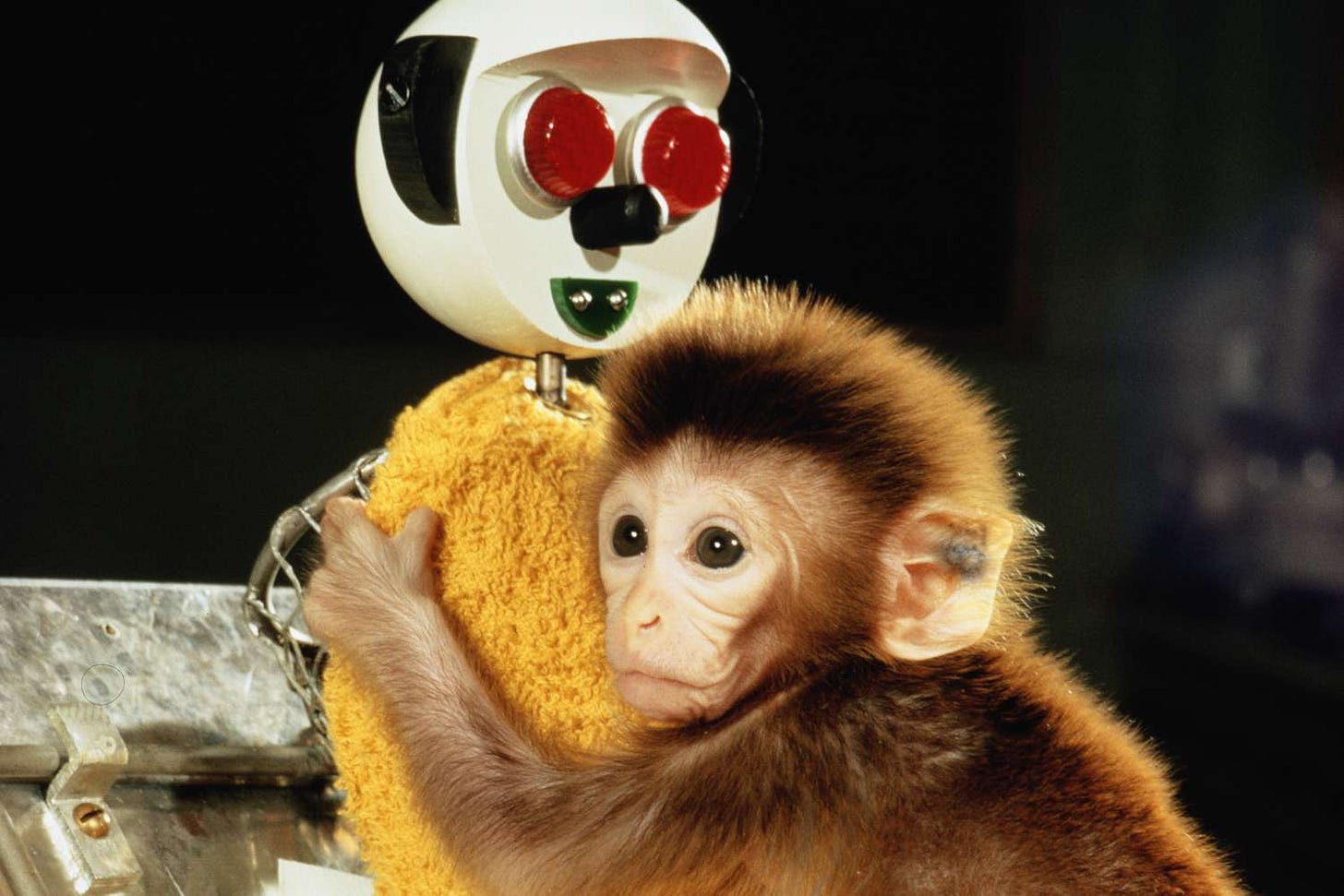

The monkey crouching at the skeletal mother’s feet mirrors that fracture. It pulls me back to Harlow’s experiment of cloth mother and wire mother, a devastating model of attachment where the soft surrogate offers comfort but no nourishment, and the cold one feeds but never soothes. The infant monkey clings to the cloth mother, his face, his eyes carry the knowledge that nothing is safe but that thin layer of softness is all he has. That expression is familiar to me.

We are born wired for safety and softness, and our mother becomes our first terrain to navigate. We attach to survive, not only to warm, nurturing mothers, but also to mothers who withhold warmth. Even to dangerous ones who punish and harm. Her landscape teaches us how the world will receive us: whether we will be welcomed into warmth and abundance or pushed into a cold, barren distance.

At first, I recognised myself in the monstrous mother of Gilded Garden. Not because I ever withheld nurture, but because that is how I saw myself at my lowest. After birth, I discovered a terrifying side to me that appeared late at night when I was alone and exhausted, unable to soothe my child to sleep. Blinding rage turned me into a madwoman panting and growling, fighting back my impulses. Overwhelmed by shame, I saw this as a personal failure.

I went to my mother for reassurance, but I wouldn’t find it there. She had little sympathy for my rage. She told me she never once felt frustrated with her babies. Her response surprised me, because my memory is full of her sharp and unpredictable rage. My fear had always been becoming like my mother.

For her, my anger was baseless, a familiar pattern of denying emotion to centre her own. My mistake was hoping for a different outcome, thinking she could finally validate what she was never able to hold. But her denial made something clear: I wasn’t repeating her. I was confronting parts of her in myself, parts she could not own. My rage didn’t make me dangerous; it exposed how unsupported I was now, and how I had never been held in my own overwhelm.

And then I recognised myself not in the monstrous mother but in the child, the one looking up at his mother with something tender and terrified, mirroring the monkey crouched at her feet.